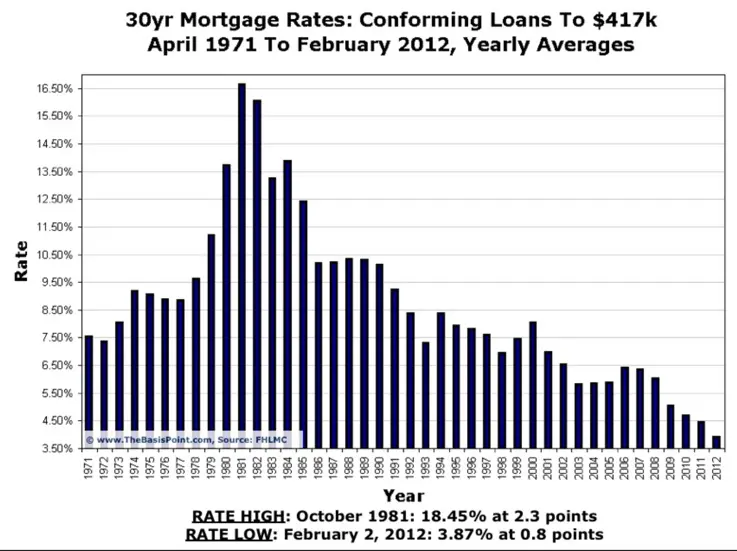

When I got my license in 1993, interest rates were 7.5%.

By the end of 1994, interest rates were approaching 9.5%.

When the market really got rolling in the early 2000’s, interest rates were still hovering around 8%.

In 2008 (the year the market crash began in earnest,) mortgage interest rates crept up near 7% during the summer before falling quickly.

In 2009, rates fell below 5%.

In 2011, rates fell below 4%.

The market has stayed + 4% range for most of the last several years and despite numerous predictions that rates will begin to rise, they really haven’t.

Sounds insane, doesn’t it?

When every market crashed in 2008, the Federal Reserve took the unprecedented action of flooding the market with cheap money. They reasoned (and they were largely correct) that the banks would stop loaning their own money in a market where assets were losing value rapidly and they needed to make cheap money available to prop everyone (and everything) up for while. The Fed did everything they could to flood the market with liquidity by dropping their rate to 0% and FORCING money into the system via the Quantitative Easing programs.

As market watchers, we get a lot of questions about interest rates. Will rates go up? Down? Flat? Should I lock in? Should I get a fixed rate? Adjustable? Hybrid? What to do??

And now, with the following disclaimer – this post is filled with many oversimplifications – here begins the post about interest rate fundamentals.

What is an Interest Rate?

An interest rate is nothing more than a rate of return extracted from the lender when they loan money to a borrower. In theory, the lender should receive compensation (interest) that is consistent with the amount of risk the loan carries.

Lending money to a doctor to buy a home is (in theory) far less risky than loaning it to your unemployed cousin who wants to start a llama farm … and thus the interest rate you charge should reflect the difference.

In its simplest form, an interest rate is made up of three primary pricing components:

- The ‘Pure Rate’

- Repayment Risk

- Inflation Risk

Each is discussed below.

The Pure Rate

What if, as a lender, you knew that there was absolutely no chance than you would not get paid back and that when you did, the money you get back would be worth the same … what rate would you charge? That is the definition of the ‘Pure Rate’ of interest.

I have seen studies discussing this concept and generally speaking, they isolate the Pure Rate at somewhere between 2 and 3%. In a very simplistic way, you can imagine the Pure Rate of 2% as the floor for all interest rates. Any interest rate above 2% is due to risk factors over and above the Pure Rate.

Repayment Risk

So, using the cousin and the llamas example from above, assume you loaned him $50k to buy some land and some llamas. What do you think the likelihood is of getting your loan back from him? My guess is ‘less than 100%’ So in order to compensate you for the substantial risk, you should charge your cousin a high rate of interest for the loan to buy the land and/or llamas.

Generally speaking, banks like to loan against owner-occupied single family housing. Why? Because it is a relatively low risk to do so.

Banks (more or less) figure that when push comes to shove, you will make the house payment before you make your rental property payment or your boat payment. Additionally, if you don’t make the payment on your home, they can take it from you, sell it, and get their money back. Traditionally, lending against housing is a pretty safe bet for banks (2008 – 2011 aside.)

(Now, for this post, we are ignoring the impact of many underwriting factors on the repayment risk. Suffice it to say, down payment, loan limits, asset types, the GSE’s (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Ginnie Mae) all can impact rates as they all influence risk to some extent. But generally speaking, the difference between a Maximum FHA loan with Mortgage Insurance and a Conventional Fannie Mae 80% is less than 1% in APR.)

So just know that the bank making you a loan secured by the home you are buying is historically a pretty safe bet for them, despite what recent memory tells us to be true.

Inflation Risk

We have all head the stories from our parents and grandparents … ‘I remember when gas was a quarter and a soda was a nickel.’

To illustrate, if you took out a mortgage in 1985 (30 years ago) and made your last payment today, you would have paid the bank back with money that used to be worth far more:

- gas was $1.09/gallon in 1985

- the average new home cost $89k in 1985

- the average new car was $9k in 1985

Pretty amazing, huh?

So it is safe to say that the value of money has changed over time – and the difference between what money is worth over time is called ‘inflation’ (or deflation, if prices go down.) Imagine loaning someone money for 30 years and then getting it back … what would it buy? Far less, that is for sure, so you better charge for it.

So when a bank commits to lending you money for 30 years, they need to make sure that when they are paid back, the money they receive back has the same value as it did when they lent it to you. Know that the rate they they charge you is reflective of what they feel their money will be worth when they get it back.

Pricing Mortgage Interest Rates

So how are mortgage rates priced? Think of it as adding the three components together:

- The Pure Rate + Repayment Risk + Inflation Risk = Interest Rate

Well if the ‘Pure Rate’ is largely fixed and the Repayment Risk is pretty small, then the difference must be inflation, right?

Yep.

When you see loans in the 3 – 4% range, what is really being said is that the expectation for prices for the core goods and services in our economy to rise substantially in the immediate future is relatively small. And given the recent upheaval in the Chinese stock market, the likelihood of the world economy getting overheated again (at least for the foreseeable future) is pretty small and thus, rates should remain relatively low for quite some time.

The Fed vs. ‘The Market’

One of the most commonly misunderstood parts of interest rate pricing surrounds who is actually doing the pricing of the rates. Many people incorrectly assume that the Federal Reserve sets the rates – which is not true – mortgage interest rates are set by a mysterious force we call ‘the market.’

So what is ‘the market’ you ask? Currency exchanges, the bond market, Wall Street, The Federal Reserve, both large and small banks, puts, calls, options, derivatives … all are in some part an input to the overall market and have an impact on the price of money. These entities constantly look into the future and either buy or sell the right to money at specific prices based on their version of where they think the value of money is headed.

When money is in demand and supply is fixed, interest rates will tend to rise. Conversely, when the demand is low and the supply is higher, then the prices will tend to drop (think 2012.) The Federal Reserve has the ability to increase or decrease the supply of money to INFLUENCE the rates, but they do not set them. When you see the 6 o’clock news talk about the Federal Reserve announcing QE II or the leaving the Federal Funds Rate alone, they are simply using the tools they have available to hopefully increase (or decrease) the supply of money (and its price) in hopes of properly supplying the needs of the capital markets. It is an amazing dance to watch.

But to emphasize – the Federal Reserve cannot dictate the price of money, only influence it. Imagine trying to drive a car at a constant speed without using the brakes and you will know what it like to be The Fed. You can speed up by giving the car more gas and you TRY to slow down by downshifting or taking your foot off of the gas, but ultimately, things like gravity and wind and road conditions (or crashing into a tree) are what will make your car come to rest. But thinking the Federal Reserve sets your rates is technically incorrect despite many’s belief.

Long Term vs Short Term Rates

Continuing the theme from above – no interest rate discussion would be complete without pointing out how long term and shorter term rates are priced.

Basically, as a borrower, you have two mortgage product options – fixed rate products or adjustable rate products. As one one would expect, a fixed rate mortgage has a rate that stays constant over the life of the loan while an adjustable rate loan contains language that allows the rate to adjust at specific intervals based on a specific index. What is really happening is the risk of inflation is being redistributed depending on who has the right to the rate and for how long.

In an adjustable rate mortgage, the borrower carries the inflation risk by agreeing to allow their rate to periodically adjust to market conditions. In a fixed rate mortgage, the lender carries the inflation risk as they CANNOT change the rate, even if inflation increases. It is why you typically see adjustable rates trade lower than fixed ones.

An interesting note is that in recent history, the difference between the adjustable rates and fixed rates (sometimes referred to as the ‘spread’) has been extremely small. Why? If you guessed ‘low expectation for inflation’ then you are beginning to get the hang of this!

Summary

If and when we being to see rates rise, it will be for one of the following reasons:

- ‘The Market’ is seeing the global economy is heating up

- The Federal Reserve decides to decrease the money supply

- The Federal Reserve decides to increase the rate at which they charge banks to borrow money

And specifically, if you see the long term rates rise, it is because the market is beginning to expect inflation and if you see short term rates rise, it is due to the Fed trying to influence the market.

The interest rate markets and pricing models are extremely complex and those who successfully buy, sell and loan money for a living are very astute. That said, even if you are not a professional, having the ability to understand the correct way to finance properties can save hundreds of thousands of dollars over your lifetime. Spend some time understanding interest rates … you will be handsomely rewarded for it.